Even though I’m a family physician, and have been for over twenty years, it wasn’t until I started studying trauma deeply that I understood just how little psychotherapeutic intervention we learn in training. Even if somebody studies something like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or motivational interviewing, that’s really intended for people who have stuck negative thoughts outside of trauma or require lifestyle modification. When you’ve been through trauma, the symptoms are adaptive, and it takes a different route to shift.

One of the first books that I read was Bessel van der Kolk’s huge tome The Body Keeps the Score. I learned a lot, especially the academic research components to it. But I was not seeing it through the eyes of a survivor, who sometimes find it triggering in his use of language, and overly research-oriented. The next book that I found the most useful was Judith Herman’s Trauma and Recovery, which takes a practical and feminist perspective. In it, she describes three phases of trauma recovery that I believe to be a very useful cognitive construct.

Phase 1 she calls Establishing Safety, which is where you develop the relationship with the therapist and learn how to modulate your own nervous system. When we have activated trauma in our body, it keeps us stuck in sympathetic tone, or “fight and flight.” This looks like restlessness, agitation, or a racing mind. It’s your body wanting to run away from or struggle with the problem, not usually possible in modern times. When this gets overwhelmed, then the body shuts right down. This is a parasympathetic frozen state, not a parasympathetic calm state. These trauma responses mean that the nervous system is in distress, and learning how to stay in a more comfortable state is the first step in trauma recovery.

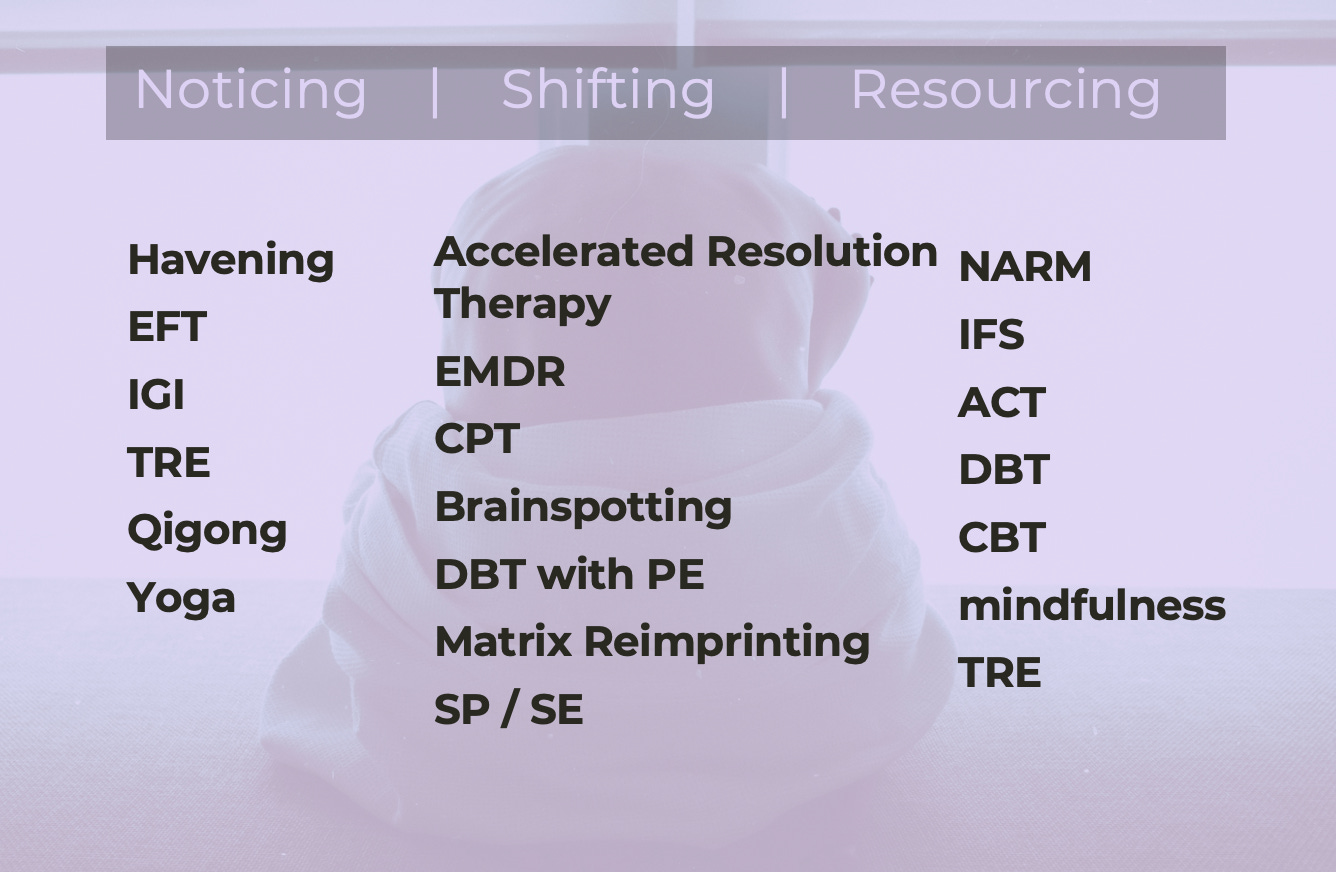

I called this stage Noticing, because the goal is to take a more observing stance to the experiences of your mind and body. Once you’re not so enmeshed with what’s happening, you are far better able to shift them.

The second stage, Dr. Herman calls Remembrance and Mourning. This is the stage where processing takes place. Remembering fragments of the event, which is generally what’s available to us. Trauma memories are not stored in the same way that regular memories are. If I were to ask you what you had for dinner the night before, you could answer very calmly that you had chicken and salad. You might have a brief experience of the tastes or textures as you recall the memory, but rarely would there be an emotion associated with it. Trauma is stored differently, and all of the associated sensations generally show up in your amygdala, which produces rapid responses. It’s why, if you are triggered by a sound or a person, your amygdalas send you into dysregulation very quickly. It’s like a reflex. So changing those associations in the amygdala, getting rid of the emotions and physical sensations and construct attached to the memory, is the key to recovery.

There are many different modalities that work for this stage of treatment; my favourites are Accelerated Resolution Therapy (ART) and Matrix Re-imprinting, but many people use others like Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT). EMDR is also very popular. I prefer the ones that I have studied because they are very short, which means that there’s not as much anticipatory anxiety between sessions.

I called his phase Shifting. Sometimes we just dip our toe into it—shifting an experience that’s more recent and less activating—first. But it’s teaching the person that, even though their brain has been locked into these processes for a long time, it’s not an inevitability. Through neuroplasticity and brain rewiring, they can be changed.

The last stage, Dr. Herman calls Reconnecting. It’s when you establish your new life and identity and patterns. Once the trauma responses are not in the foreground. It takes a lot of energy and attention to be locked into these patterns! Once they are lessened, if not gone, you have to reestablish how to show up in the world in a way that you prefer. It sounds easy, but it’s often not. Once you’ve lived for a decade or more with those reflexes stuck, the triggers being avoided, and the hypervigilance taking up a lot of energy… it’s hard to know how to be afterwards.

I called is stage Resourcing—because a lot of it is establishing physical, social, and emotional resources to manage a new way of being.

When I was a family physician, I didn’t think this was possible. We weren’t given a medication to manage PTSD and pharmacological approaches are the most common tools in a physician’s toolkit. It wasn’t until I started studying all of these therapeutic modalities myself that I started to feel competency around PTSD. Having hope for my patience in this scenario, and my ability to be attuned to their experiences, is part of what has allowed me to become an effective clinician.

I would argue this is one of the most important skill-sets that generalist physicians can learn. And it doesn’t really matter which tools you choose to use, but having an understanding of these three phases, and at least one or two tools in your skill-set allows you to manage the underlying cause of much of the symptoms that we see in our offices. Having hope for our own capacity, and then sharing that hope with those whom we serve. It’s a large part of the purpose behind my book—to offer those tools.