There are a lot of news stories about dementia right now. And of course, medical doctors can’t comment on public figures, but we can certainly share the facts.

There are two main forms of dementia.

Alzheimer’s Disease is based on (1) new plaques and tangles that form and (2) lost neural connections in the brain - these are not easily visible on neuroimaging. Amyloid PET scans and spinal fluid testing for proteins like amyloid or tau are not available everywhere. We used to say that it could only be diagnosed on autopsy. McGill made this excellent diagram of microscopic changes:

The plaques are made of a protein called amyloid. They selectively show up in the places of the brain that store memories, like the hippocampus. But in the final stages, the entire brain shrinks, which is when it will show up on scans. Causes are likely multifactorial, but we have found a few genetic markers that make the disease more likely.

The hippocampus pattern means memory loss is one of the more typical signs of Alzheimer’s disease. For most people, they can remember the past much easier than they can form new memory. Eventually - difficulties finding words, making decisions, and even remembering simple tasks can be affected. In later stages, people have trouble recognizing family members, and can even have delusions or paranoia. At the end of this illness; they might forget how to walk, talk, and feed themselves.

So far, most of the medication’s can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, but we do not have anything that stops it. There are now two medication’s administered through an IV that targets the amyloid plaque buildup, Kisunla and Leqembi. The former is available in the US, after a single study showing the disease progressed 22% more slowly than somebody who who received placebo. Neither are available in Canada. Side effects could include swelling in the brain or bleeding, which happens in 20% of patients.

The other most common cause of dementia is vascular disease. This is like a series of strokes or mini-strokes in the brain, when blood flow is compromised and oxygen is not delivered. As you would imagine, risk factors are the same as any other condition that narrows your arteries so would include diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, and hypertension.

Because vascular dementia is a series of events rather than a gradual change, we often see this as a step-wise decline rather than a slow progression. When there’s a clear stroke that involves other parts of the body (weakness or speech impairment), the diagnosis is more obvious. If a person has a condition called atrial fibrillation, or an abnormal heart rate, this cause of cognitive decline would be more likely. Because the causes are different, the treatment is different here. If it’s a blocked artery, then sometimes aspirin would be prescribed. Managing risk factors like keeping blood sugar and blood pressure under control are also helpful.

Since there’s no single imaging test that can prove the diagnosis of dementia, we rely on a number of mechanisms. We might do imaging of the brain and look for evidence of amyloid plea or vascular changes. But these aren’t sensitive, meaning that they show up every time - or specific, meaning that, even if they are present, it does not mean that you have the disorder.

There are two tests that I studied in order to examine memory. The first is called the MMSE or the mini mental status exam., Once the inventor died, his family decided that they wanted to make more money off of the test and so now they charge every individual or institution who wants to use it. So it has fallen out of favor. Which is too bad, because it’s very easy to remember, and I don’t even need to use the sheets anymore.

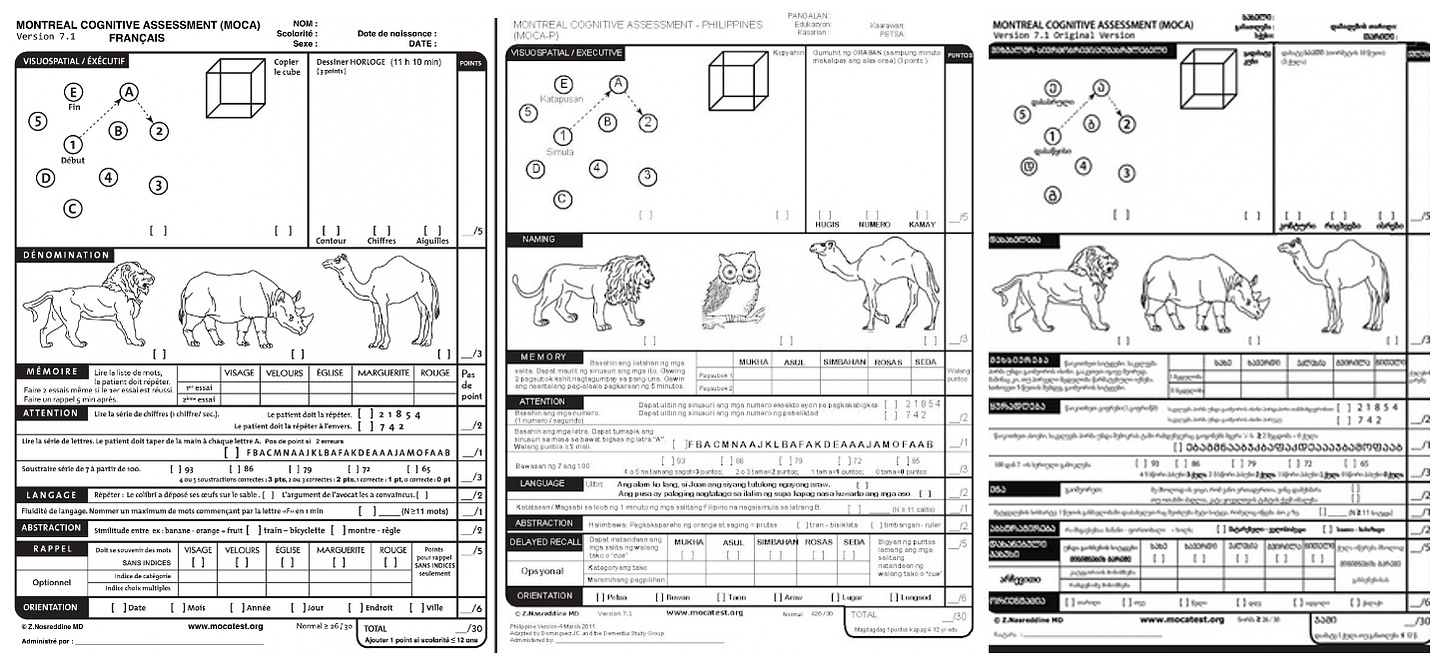

The second common test is the MoCA, or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. What I really like about this one is how there are different versions of it so the patients can’t memorize it so that they do better the next time it administered. For example, they might have to name as many words with the letter F as they can on one test, and the next time they come in, it’s a different letter. There are also adopted versions for hearing or visual impairment, low education, and using it over telehealth. The organization requests that anybody who uses this test would get trained in it first.

Here are versions of the test in French, Filipino, and Arabic:

Frankly, getting a perfect score on these dementia screens would be quite easy. They both measure drawing skills to look for visuospatial abilities. In fact, drawing a clock (and setting the time to 10 minutes after 11 o’clock) is something that is commonly used as a screen. Which is very interesting considering how more people are familiar with digital clocks then those with hands (anyone under age thirty?). Each test also has naming common objects - in the case of the MMSE, it’s objects like a pen or a watch and in the MoCA, it’s drawings of animals. Each test will ask the person to remember five words, both immediately and a couple of minutes later. Both exams have a moderately hard mathematical test. They also each ask to repeat a sentence and ensure the person is oriented to time and location.

Both tests have been validated through research, but for many people dementia can progress before they would necessarily have their score affected. For others, issues like language or sedation can make the testing difficult.

The second thing we do, and this is more common for folks who are hospitalized, is we might send them to occupational therapy to evaluate how they do on their activities of daily living (ADL and iADL). So they would have to do functional testing to see how they would handle manoeuvring a kitchen, getting some banking done, or mailing a letter.

Lastly, we would inquire to people that they are spending time with as to their impression of memory and cognitive capacity. Even personality changes can herald the sign of dementia, especially one called frontotemporal dementia, which is more common in Parkinson’s disease.

Overall, both the diagnosis and management of dementia are complex. We often rely on specialty physicians like geriatricians to help in this regard. But because we don’t have an actual cure, it is sadly something that happens to many people as they age - statistically, about 20-25% of 80-year-olds will have some measurable form of dementia. This reaches 33% at age 90.

Personally, I think it’s a good argument to have annual cognitive testing for anybody who is in the workforce over the age of 75. We do it for driving. Why aren’t we doing it for all critical occupations? (BTW, this is not endorsing one candidate or the other - both exhibit some symptoms. It’s just a realistic view that people’s brains age.)

(Are you following my other Substack? I released an article about treating trauma this week - you can find it here. I’ll do more trauma-related posts there and more systems-change and miscellaneous ones here)